Subject Area: Sociology

Chameleons in the Attic of my House – Coca Cola Girls and the Unreasonable Effectiveness of Canned Laughter – Fighting Queen Elizabeth

Chameleons in the Attic of my House

I can still somewhat recall the day my biology teacher (and God bless her) told us all these super cool stories about mimicry in biology when I was in secondary school (high school for my North American readers). The idea of a Chameleon mimicking the background color of, say, a tree or a grass has stuck in my mind ever since. This is perhaps because of inadvertent practical exposure to the concept: I was walking down to the school gate, after closing hours, on a sweltering day; a friend of mine started screaming his lungs off, literally yelling, informing us to come to see a Chameleon – the animal our biology teacher mentioned the other day in class. Lo, and behold, we saw this tiny thing and couldn’t believe our eyes. How is this even possible? The skin color is changing right in front of our eyes; we were elated, we yelled, we jumped, we screamed, and we spread the good news. We must have frightened the Chameleon so bad that it never came back, but we didn’t fail to suspect a couple of folks in the class who could have killed the poor animal.

Now, If I tell you that biological mimicry is the only place we see imitation in nature, I will be a bloody liar – but I am so cool that I would rather not be one. And what am I saying here? I am saying that if there is anything like a theory of everything in nature, it will be wrapped in imitation, it will be dripping of imitation, it will be soaked in imitation.

As adumbrated in my earlier example, biological mimicry is reflected in Charles Darwin’s work, for example, and its role in survival, adaptation, and evolution. Also, people before Darwin knew of mimicry since they were not walking around blindfolded. For example, Aristotle knows of Octopus mimicking the color of stones, Pliny reported mimicry in Chameleon, and so on.1 While this ‘imitation’ abounds in lower animals, it is superbly and distinctively unique in humans. I will explore imitation in humans via the Girardian philosophy of anthropology and history, where imitation is called mimesis, mimesis because it’s a little more complicated than mere imitation. But, in many ways, it explains everything.

Coca Cola Girls and the Unreasonable Effectiveness of Canned Laughter

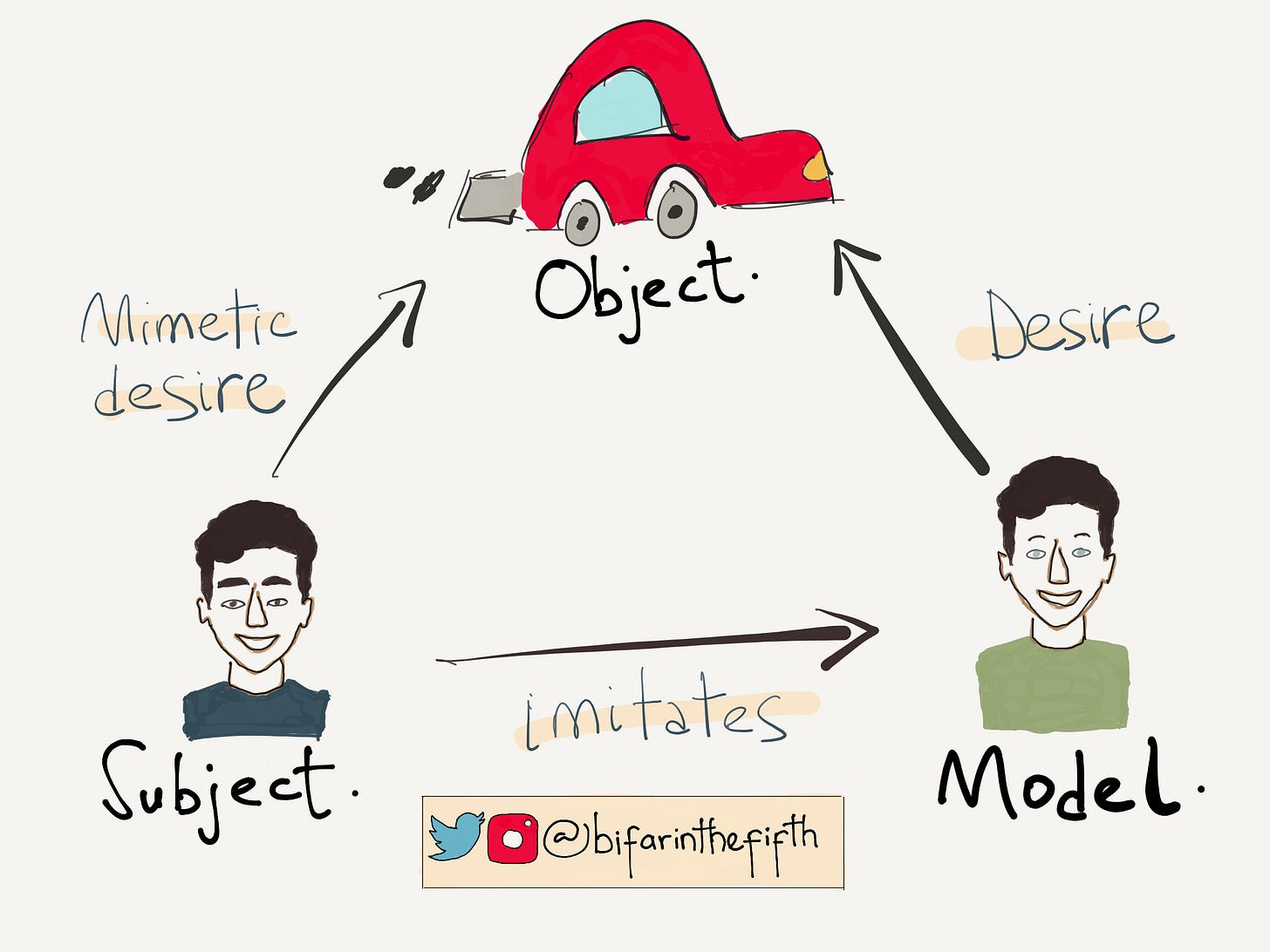

At the heart of Rene Girard’s mimetic theory is desire – mimetic desire. Beyond our immediate needs, such as food to survive, or protection for safety, it’s hard to say anything positive about the truthfulness of the originality of our desires. We imitate the desires of others, so desire – according to the Girardian philosophy – is mimetic.

This structure gives a simple triangular framework where a subject imitates a model to acquire an object.

Everything seems to be fine when the object is limitless, say like the acquisition of language. However, it’s not unusual for hell to break loose when the object is limited, and many people want it. This explains the vast amount of violence in human history, which remains in many forms today. This simple idea explains the origin of religion, culture, political authority, et cetera. But I am moving too fast; we need to do a little more groundwork before blowing the whole thing up.

Let’s see how simple mimetic desire works. Put some kids in a room with identical toys, and it’s only a matter of time that you see a bunch of kids quarreling over a toy while being surrounded by unused identical toys. But it isn’t only kids, believe me.

Say, a blonde girl lives just by your street, you think she’s OK but nothing crazy. Except that on resuming in your new school the following fall, all the big guys on campus couldn’t stop talking about her. They all want in. And for some reason, she stopped looking OK, and now she becomes the hot girl down the street, drop-dead gorgeous, that kind of thing, and the best part – you want in too. Nothing about the girl changed – even maybe objectively, she grew a little uglier – except that other people you think highly of now desire her.

Here is another example: despite the critical stance of several people on the use of canned laughter in shows, studies have shown the effectiveness of canned laughter – if you listen to a show with a laughter track, you are more likely to laugh, laugh longer, and laugh often.2 In addition, a study from 2019 shows the positive modulation of humor ratings of bad jokes by others’ laughter.3 In order words, the subjects imitated the desires of others to the point that it felt real, to the point where they felt original.

Also, the reader must notice the template of modern advertisement – one never, if at all, see a product or services advertised without a model. It has to go along with the ideal model(s). This template is in response to our instinctive mimetism. And this goes way back. Take this advert from Coca-Cola’s 50th anniversary, for example; what the hell do you think is going on here – many things. One of the observations is aptly presented by a wise old man – Charlie Munger – in his almanac; he says, “the brain of man yearns for the type of beverage held by the pretty woman he can’t have.”4

Here is another, showing perhaps a grandpa enjoying coke with his granddaughter.

We can go on with several modern advertisement examples, and yet, advertisement presents itself as a paradox; one could say the anti-mimetic mimesis of advertising.5 This paradox is simply that we are sold a product on the ground of originality – to be unique. At the same time, the medium itself is contaminated with mimesis, with the goal that as many people as possible buy the product. At some point, you have to stop and ask yourself: who is fooling who?

And, if I must continue, I must end with an unlikely example – mimesis does not restrict itself to glamorous scenes. On the contrary, even on a dark subject such as suicide, human mimesis appears to flourish. So let us take on the Werther effect, and our story must start in 1774 when Johann Wolfgang von Goethe published die Leiden des Jungen Werthers.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (as the book title goes in the English Language) propelled him into the limelight while in his twenties. A novel that tells a very dark story, one must say. Young Werther started out happy until he fell in love with a lady, Charlotte, already engaged to someone else, Albert. In short, he got himself entangled in unrequited love. Over time, Werther became close to both Albert and Charlotte. When he couldn’t continue to cope with the pain, he left the town for Weimar, where he was pushed further on into his misery after he faced embarrassment from the aristocratic folks in the town and was forced to return to where he came from – to Albert and Charlotte. Except, now, they are married. His sorrow knew no bounds, especially when Charlotte had appealed to him not to visit so frequently. Finally, he decided to write Albert to borrow him two pistols one day, as he would love to embark on a journey. To which Charlotte gladly responded in the positive and sent the pistols over. Except that it was this pistol he used to commit suicide.

The book was so popular in Europe that it led to an emulative suicide streak, where it’s not unusual to find the book – The Sorrow of Young Werther – at the scene of suicides. Leading to a suicide epidemic, the authorities banned the novel in Leipzig, Denmark, and Italy in response to the imitation of the desires of a fictional character.

And this doesn’t appear to be a false signal, as many studies have documented the so-called Werther effect. In fact, in a paper just published a few months ago in PLOS One, two South Korean researchers documented their empirical analysis of celebrity suicide reports on copycat suicides. They concluded that “on average, the number of suicides in the population increased by 16.4% within just one day after the reports.” 6

Fighting Queen Elizabeth

It will be incredibly useful to say one or two things about the manner of ways to think about these varied examples of mimesis presented. Even though they fit into the same imitation framework, there are many significant differences.

We could start with non-acquisitive mimesis; we imply that the object of imitation is unlimited. This will be the case with the canned laughter example. Your laughter doesn’t take anything away from mine, especially say we are watching a show on different continents. Likewise, the imitation induced by advertisement is also non-acquisitive, so is committing suicide.

However, when the object of desire is in limited quantity, conflict is not unusual. In Girardian philosophy, this is what is called acquisitive or conflictual mimesis.

For the blonde girl living down your street, with so many men on her case, one can wager that conflict is at the horizon. If we go back to Archaic societies, three categories of things lead to violence – land, women, and livestock. This provides us with a simple and yet effective theory of violence, explained perfectly by acquisitive mimesis. Land, women, and livestock are subjects of imitations, and the particular kinds of interest are never in unlimited supply. Mimetic desire provides us a simple explanation for why humans are so prone to conflict and violence – we want what other people want except that we cannot all have it.

There is also another circumstance where mimesis can be mediated internally or externally. Internally where mimetic rivalry is the result. Externally where conflict does not ensue. How many of my readers have been envious of Queen Elizabeth ever? I will be surprised if I find any, feel free to write me if you are one. And on the flip side, I wonder how many of my readers had never been envious of their friends – I would like to hear from you too.

Your chance of conflict with the Queen of England, even if you so decide to imitate her, is almost nil. However, the same cannot be said should you choose to imitate a neighbor. The former is external mediation; the latter is internal mediation.

It must not be surprising that the greatest enemies in history are found amongst siblings, ex-friends and neighbors. Internal mediation leads to mimetic rivalry, which in turn leads to conflict. External mediation is when you decide to imitate The Queen or Martin Luther.

The closer you are to a person, the more the likelihood of wanting the same thing. Everything will be fine until there is only one instance of that thing that you both desire; if that happens well enough, be ready to fight. And the reader must find the following enlightening:

“Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s house, thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor anything that is thy neighbor’s.” [Exodus 20:17]

One can go and on with the numerous dimensions of human mimesis, but I must stop at this junction. Stop by saying that just the same way animals wouldn’t be able to survive if they had not evolved to pick up some mimicry behavior; it is hard, if not impossible, to speak to a human civilization without imitation. How do you acquire language? How do we acquire culture? In far too many discussions of this kind, the point remains – what helps you can also hurt you.

References

Robert B. Cialdini, Influence: The Psychology of persuasion. Pp 115.

Charlie Munger, Poor Charlie’s Almanack Pp 287

Wolfgang Palaver, Rene Girard’s Mimetic Theory Pp 69