Subject Area: Modern Work

Free time is de-motivating – How to stretch your saturation point – Emails are not good for your health.

If you are a knowledge worker today, let’s face it, you are most likely facing the heat: so much to do, so little time, and an unprecedented level of distractions, especially from the most recent media on the block. So, after all, it’s not a bad idea to have a manual, or at least a working philosophy guiding how you work. This will be the subject of this essay — a way to approach work today, or if you will, how to work in today’s storm of distractions.

Free time is de-motivating.

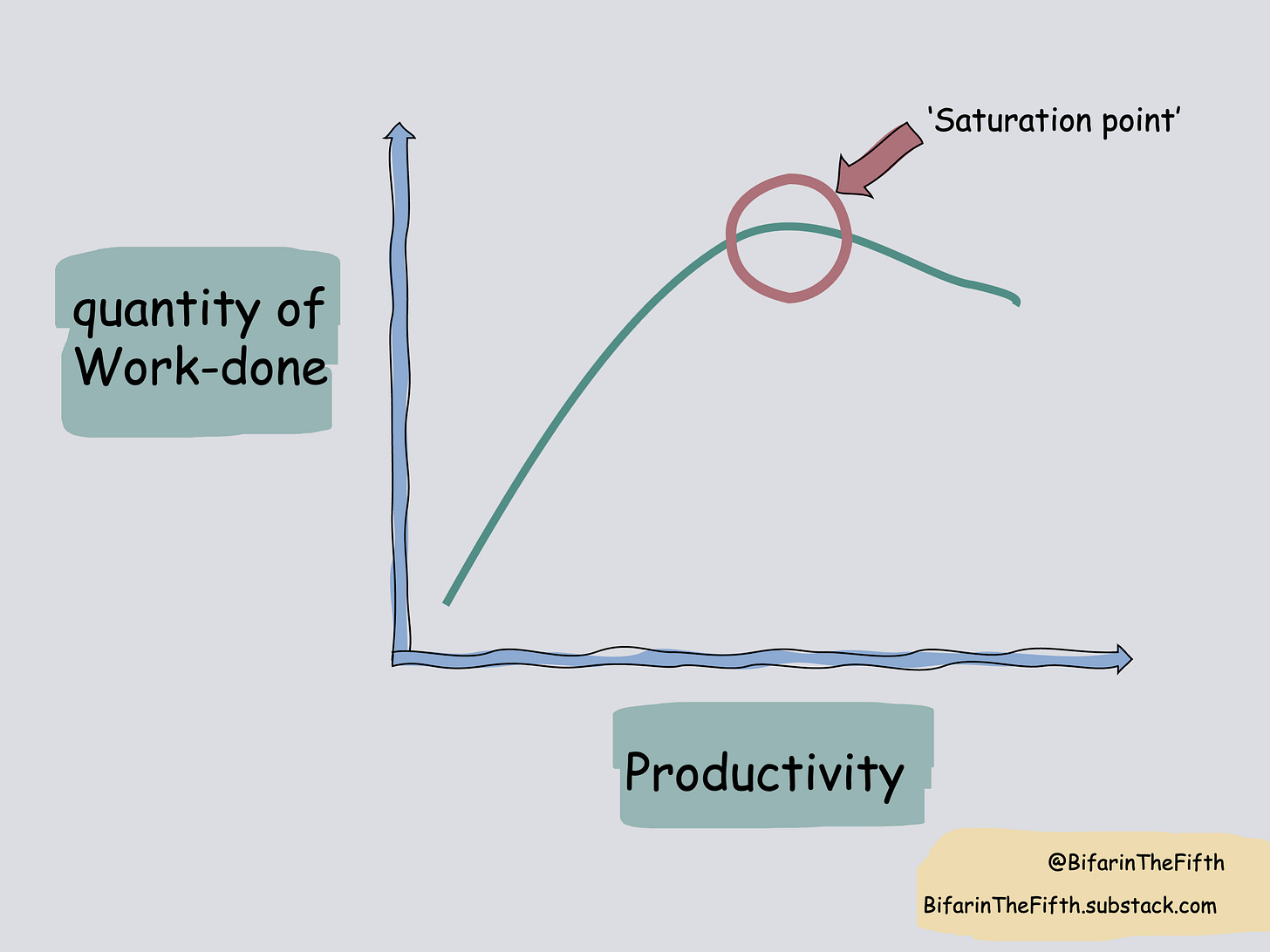

One of the things even a cursory observer of work ethics will realize is that – there is a direct proportionality between the quantity of quality work-done and productivity. The more work you do, the more productive you become (this goes without saying), but importantly, the more productive you are likely to be. Up to a point. Beyond this point, chaos sets in.

This is perhaps the main idea behind the wildly popular advice (heuristic, I will say) if you want to get something done, give the busiest person in the room. It's also related to the 'resource curse' psychology – simply put, free time can be demotivating.

On the other hand, a busy person is more likely to be reliable because the act of busyness (busyness in the context of getting quality work done) makes them so. When you do more of a thing, you get good at doing the thing, and this does not exclude being good at getting things done. There is a motivation motif here, and there is also a ‘better project manager’ component. A ‘free timer’ loses both.

Going back to our graph, even a conscientious, productive person has a limit, and let’s call this point on our graph, for lack of a better term (and I will be borrowing from chemistry), the ‘saturation point.’

The saturation points can be easy to detect, and here are a couple of markers that can help. 1) a sharp transition from well-organized scheduling to a chaotic one which becomes quickly apparent in lagged turnover of to-do lists if you use one. And 2) sleeping less than you will otherwise do.

So, one of the utmost goals for a knowledge worker will be to delay this saturation point as best as possible while keeping the quality of work intact. And in case you want to know, it is not an easy thing to do, not least in the current clime riddled with deadly rabbit holes.

How to delay your saturation point

Check emails at most three times a day.

Or creative work is better than reactive work. When email was invented, very few people intuited that it would keep knowledge workers from doing their jobs one day. What is supposed to be a tool of efficiency for many has become a tool of inefficiency; that is, when it’s not making your heart race literally. Cal Newport, a Computer Science professor at Georgetown University, argued that e-mails are making us miserable in his book a world without email; here is an excerpt:

“The history of technology is littered with cautionary tales of what goes wrong when new tools yield superficial convenience, but are poorly matched with fundamental human nature. E-mail is arguably one of the best examples of such unintentional consequences in recent history. It’s useful, of course, that we can communicate instantaneously, with almost no friction or cost. But humans are not network routers. Just because it’s possible for us to send and receive messages incessantly through our waking hours doesn’t mean that it is a sustainable way to exist.”

When I was in graduate school, I began to feel the heat. The constant switching from emails to deep focused work when you have experiments to complete and computer codes to write. The important work should take priority: check your emails at most three times a day. And preferably not the first thing in the morning; you want to be creative before being reactive, mainly because willpower is a finite resource; use it on the most essential stuff when the tank is full.

Your To-Do List Doesn’t Like you.

Have you ever attempted to write a list of things you want to do in the next eight hours but couldn’t manage to finish it in a week? Well, we have all been there. There is something radically different between writing something you want to do on a paper and actually doing that thing. In the psychological parlance, we will say you are very much prone to optimism bias. A bland list is not the best, but scheduling can make things better – putting time against things. Not a particularly easy thing to do. But, oh well, what other options have we got? Except to add that nobody should be a slave to a scheduling list, there ought to be room to wander, to have unstructured freedom. You want a suitable balance between Apollonian and Dionysian scheduling, to invoke Greek mythology.

Finish it if you start it.

Or only handle it once if the task is modular enough. Handling the same thing multiple times is one way to get into a gumption trap. If there is any magic to getting things done, this will be one of them. And there are caveats; sometimes, you can leave tasks to cook in your head; for example, I rarely write my essays in one go and then publish it. I leave it to simmer; sometimes for many weeks, then I get to it again. Also, sometimes you just can’t finish things in one go.

There is something called a barbell, and it works.

It can work magic. In finance – investing in high-risk (but highly profitable, when it is) portfolios and in low-risk portfolios (with a low dividend, safety largely guaranteed). In bodybuilding – the maximum weight that one can carry followed by intense rest. And since we are talking about productivity – deep, focused work followed by deep rest.

Note that focused work does not lend itself to susceptibility to clicking baiting, checking emails, Slack, Instagram, working in 5 minutes increments, or worse, cursing a follower on Twitter. Far from the best practices. Focused work means going deep! Working on a problem for a long time (without interruptions) followed by, preferably, deep rest. I have heard people swear to be able to go deep while still checking in on Instagram or Twitter every other minute. In my opinion, those folks haven’t experienced what deep work is. So, at the risk of repeating myself, there is something called a barbell, and it works.

And to piggyback for a little bit, constant task switching usually hurt productivity because of something called the attention residue. It simply means there is a residue of attention from the prior unfinished tasks that follows you around, and hounds you. Say you are writing a paper, and for some reason, you just decide to send out a tweet or just glean the subject of an email, and then you switch back to your paper. That is more than enough to get things tangled up. So, it’s much better to work in this alternating focused work-rest fashion. One popular technique is called the Pomodoro technique, a time management technique developed in the 1980s by Francesco Cirillo. It typically involves a period of focused work, originally 25 minutes, followed by a break. This gives one Pomodoro, named after Cirillo's tomato-shaped timer in college. Multiple Pomodoros are then chained together, say four times, followed by a long break.

In the spirit of focused work, Picasso was once quoted to have said, “While I work, I leave my body outside the door, the way Moslems take off their shoes before entering the mosque.”

Practice fixed scheduling.

Parkinson’s law: “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.” Put another way: “The amount of time that one has to perform a task is the amount of time it will take to complete the task.”

I like Isaac Asimov’s version better, “In ten hours a day, you have time to fall twice as far behind your commitments as in five hours a day.” Practice fixed scheduling.

Rest.

When I was in college, I was a rapper, a soccer goalie, and was at the top of my class almost throughout my stay. The problem is that Nigerian higher institutions make participation in extracurricular activities utterly unbearable.

So, it was tough keeping up. I worked, and worked, and worked, and worked. I soon internalized a lousy idea that poor sleeping pattern was a marker of seriousness.

Fortunately, I realized soon after college that my priority in life isn’t to win a game but to win in life (which composes of many, many games). And that when one is going on a very long journey, ‘hard work’ can be counterproductive.

What am I saying here?

I am saying that accomplishing your goal requires you to wake up in the morning and work – it requires you to survive.

“I have realized that somebody who’s tired and needs a rest and goes on working all the same is a fool” I didn’t say that, the great psychoanalyst Carl Jung did.

To conclude, I will turn to two unlikely persons. 1) Charly Munger, the very wise nonagenarian, Warren Buffet buddy, and Berkshire Hathaway vice-chairman. 2) Carl Gustav Jacobi, the German Mathematician. Charly is famous for the quote, probably borrowed from someone else, “all I want to know is where I’m going to die, so I’ll never go there.” The latter is also quoted to have said, ‘man muss immer umkehren,’ meaning invert, always invert. The common denominator of these two aphorisms is inversion. As in algebra, turning problems around makes one think better. So instead of asking, how can I be productive, you can ask, “how can I [insert your name here] on this Monday morning waste my time, such that I get nothing done, and such that at the end of the day, I will feel miserable.”

So here we go: Spend all your day reading emails, work in five minutes increments (with constant interruption by your Twitter or IG feed), never schedule focused work, spend zero time ahead of work to decide how exactly you want to spend your time, get exactly 3 hours of sleep every night, eat a crapload of sugar, and so on.

Friends, if we are to be productive as knowledge workers in the 21st century (granting that we are all working in a storm of distractions), those are (some of) the things we must avoid.

Profound. Thanks for creating and sharing. 🫡