Subject Area: Philosophy

The Labyrinth of Philosophical Truth – Solipsism: Arguing from the Dead – Realist, Antirealist, and the Rest of Us

The Labyrinth of Philosophical Truth

"To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false; while to say of what is that it is, or of what is not that it is not, is true." I didn't say that Aristotle did, and what do I think? I think that is true. Perhaps that should be the end of this essay; I should stop writing and get back to the piece of software I was writing or, better still, play soccer; however, one could only wish that life is more straightforward.

First, let's battle an assumption head-on, does truth exist? And what do I think? I think our intuition can guard us here: there is a truth about anything that we can conceive – there has to be a judgment on that thing. And a correct assessment leads us to the truth. And what is correct? Correct is that which is right. And friends, I hope we won't start a quarrel at this point.

However, if we intend to quarrel, how do we even begin to show that truth does not exist. To show that truth doesn't exist, one will have to offer – or at least effectively – argue for the existence of a truth, namely that 'truth doesn't exist.'

Anywhere you are standing on the field, the battle is lost – the existence of truth is axiomatic.

And what can we say about the truth? Perhaps we should start with a coherence theory of truth. For coherence, the trueness of a proposition is nested in other propositions. That is, when an idea coheres, it does so in a system of belief, as opposed to correspondence theory that claims to check ideas against reality (more on this later). And, of course, coherence theory is vulnerable at first sight: what is the validity of the other propositions in which it is nested? Wittgenstein gives a smacking objection: "If what seems right is right, that just means we can't talk about right."

Next is the correspondence theory. It dictates that what is true is that which corresponds to what is. For the first 'what is,' we mean thoughts/words; for the second – reality. But then, what does it mean to match, especially when we have multifarious realities: law, science, ethics, mathematics, art. Are we to take a detour and speak to a theory of matching? And what tells us that we are making contact with reality? Isn't this an assumption? Whether you think too much of these philosophical objections or not, it is a prevalent theory of truth.

One more, and then perhaps I wrap this up – pragmatism. It says what is true is that which works – is that which is useful. However, that which is false could be useful, and that which is true might be far from useful. As a manner of examples: it might be useful for you to think of yourself as the smartest folk in the room, but that doesn't make you one, if in fact (now appealing to correspondence theory) you are not. Likewise, of what use is the time – to the last millisecond – that I slept yesterday night.

Next, can we know the truth? Perhaps we can, and perhaps we can't. Even worse, perhaps we can't know if we can know the truth. But then we have to decide what to believe, as we have got no options if we are to live a sane life.

And to prevent some complications that could emanate from defining truth, one could also take a semantic deflationary stance on truth. If I say "the dolphin is dark," and then I quickly added an alternate statement: "It is true that the dolphin is dark." With just a couple of seconds of meditation on the two statements mentioned above, you might begin to feel very uneasy. What is the 'true' in the second statement doing? You might want to know. Is it just hanging around?

Alas, a deflationist will argue, the concept of truth isn't very useful. We can only speak about the truth when we talk about the particular. So if you are in this group, there is plenty to talk about, be sure to grab a cup of coffee.

Solipsism: Arguing from the Dead

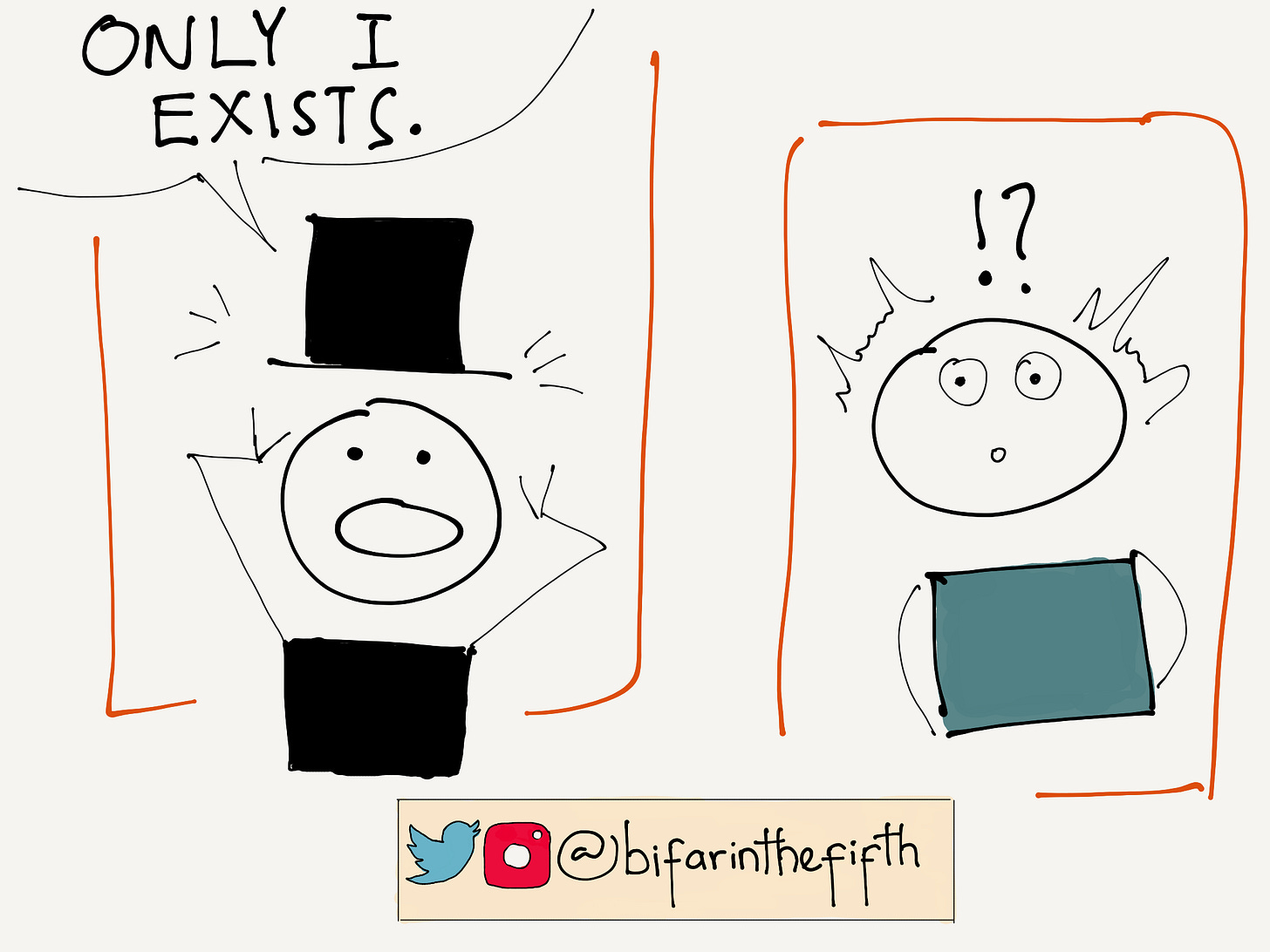

We can do metaphysical solipsism first, and if you are about it, the argument goes roughly as follows: 1) your mind is the only thing that you have access to, 2) confirmation of mind outside one's mental state is impossible, 3) therefore only your mind exists. The kernel of the argument is that there is simply no link between our mental state and the truthfulness of the existence of other minds, or if you will, the existence of other minds as such (granting the deflationary position) – including the subject with the mind. As such, a metaphysical solipsist will be fine with the following statement: "Trump does not exist." "The fellow who is reading these words do not exist," only their appearances do. etc. etc.

I think solipsism is very silly, but of course, that is not an argument; you need an argument to kill these things. It reminds me of the story of a fellow who, upon sighting a couple (huge) cockroaches on his bed, proceed to profess how much of a nuisance the roaches are and stopped there. As if to say calling roaches nuisances – which they are if they inhabit your bedroom – would exterminate them. So here you go: 1) there are no evidences of a private language. (A private language is a language that you solely develop and use, not a code that another agent can decipher, but a language woven into your thoughts.) 2) You communicate with people with a shared language. 3) If there are shared languages, other minds are needed for its use and evolution. 4) Therefore, other minds exist.

Let's say that wasn't convincing enough, you don't buy it, and you ask me: what if solipsism is true? It won't matter if it is partly because any attempt to spread the 'gospel' of solipsism will be granting that solipsism is false.

There is another, albeit a milder version of this whole solipsism business. Let me illustrate. As I am typing these words, I can see a white paper just to my left side. And then something strikes me like a thunderbolt: "how the hell do you know this is a paper?" And what does it mean for something to be a paper?

See, forget about the label 'paper' for a minute and think of that which the 'paper' corresponds to; let's call this thing Ð (breaking away from solipsism, we grant that Ð exists.)

The question now is, am I really seeing Ð? or is my mind processing Ð such that I see it as a paper? How could we possibly test this hypothesis? These questions can be deceptively tractable, so let me rephrase it: how do I know when I see Ð?

Dead-end.

It turns out that if I can 1) perceive a paper as a paper and 2) use the paper for what a paper is used for, then it is a paper. But does that disprove the possible existence of a Ð? And so on, and so forth.

This is a classical critique of the integrity of our sense perception. But there is not much to work with here, friends. To prove the integrity of our sense perception, we would have to get out of it, except that we can't. And since there are no defeaters for our sense perception, we are totally in good shape to trust it. And I can't believe I just typed the last statement. However, things will become more complicated the moment we start to talk about evolution via natural selection (more on this later).

Anyways, I hope it doesn't surprise the reader that I do believe that Trump exists. And hopefully not shocking that some folks don't.

Realist, Antirealist, and The Rest of Us

Okay. For now, forget about papers.

Let's assume that papers exist as papers, not as a potential Ð; and that science can give a true description of the observable parts of the world because we perceive the real thing. (When we talk about observable features of the world, we talk about trees, water droplets, and everything in-between.) Now, to begin to stir up some more controversies, how should we start thinking about the unobservable parts of the world?

Leptons, quarks, electrons, do they really exist as such? A scientific realist will say, "absolutely!". However, an antirealist will disagree with the word 'absolutely.' To put it a bit more precisely, a modern antirealist will be agnostic with regard to the 'reality' of an unobservable entity.

Let me take a step back and stress that both folks on the opposing side of this aisle are metaphysical realists; that is, they believe that there is a mind-independent world in which we can pontificate on its trueness (or the lack of it). That is, with regards to the observable parts of the world, both the science realist and antirealist have no dog in that fight. The reader should note that this position stands visibly in contrast to metaphysical solipsism.

Now that we have gone this far, indeed, we can't go back. And perhaps you are saying, what is all these fusses about (un)observable entities of the world anyways? Here is the scientific realist argument: 1) given that the theories of the unobservable entities had been highly successful empirically (i.e., accurate predictions); 2) it must be an extraordinary coincidence for it not to be true; therefore, 3) scientific realism is true. There goes the famous 'no miracle' argument – to believe otherwise is to believe in miracles (an uppercut for an instrumentalist).

Perhaps not so fast for the scientific realist because we can think of a scenario that will perturb the peace of the premises stated above: ontologically different theories might appeal to precisely the same evidential properties. And if it is the case that they are ontologically distinct, then it can't be the case that they are both true. Hence, scientific realism is false. So technically, we say that the observational data 'underdetermines' the theories – i.e., the underdetermination argument against scientific realism.

Let's say I am bluffing, except that I am not: take the example of the phlogiston theory of combustion, which argues that during combustion, phlogiston is released. This was believed to be true up until the 18th century. Except that there is nothing like phlogiston – it was all a lie – as subsequent research has shown, burning occurs when substances react with oxygen. This example could be cited by a scientific antirealist, arguing for the position of pessimistic meta-induction. Simply put, scientists have offered theories in the past that has failed or evolved. So why should one think that the best theory now will do better?

In addition, the reader must not miss the elephant in the room, the inference to the best explanation (IBE) motif in the 'no miracle' argument – It's screaming out loud. The argument does not prove that scientific realism is true; it only infers that it is true based on the best explanation of the 'data.' And the news isn't new: the circularity in inductive arguments still hasn't been defeated. In other words, what is the justification for induction itself, provided we still have circular reasoning in our logical fallacy dictionary? To add insult to injury – even if we grant such and such – the best explanation might just be the best explanation among a bunch of terrible explanations.

Notice how the scientific realism/ antirealism debate leads us back to the theory of truth. A scientific realist is more likely to think of a good explanation as a proxy for truthfulness. In contrast, an antirealist will think of a good explanation as a practical tool, something useful, not necessarily true or real.

Let's rest our case for now.