Subject Area: History

Are postdocs starving? – Liquidum non frangit jejunum – The king of breakfasts – Lean as hell.

Are postdocs starving?

Breakfast (noun), a meal taken in the morning, literally means break [your] fast.

A few months ago, I told a friend I had stopped eating breakfast for some time now, and he replied and asked if the inflation in the United States is so bad that Postdocs now have to starve. I allayed his fears, nothing of the sort. (It turned out to be one of those far too numerous postdocs’ jokes, after all.)

Later in our conversation, I added an interesting historical fact: during the Middle Ages, breakfast was pretty much ignored [1]. In fact, the poor are one of the main groups predisposed to having breakfast, folks who need the energy to do heavy labored work. The other categories are folks with weak health who couldn’t wait until midday to break their fast (such as kids and the aged).

Liquidum non frangit jejunum

Tellingly, Saint Thomas Aquinas, in his summa theologia, warned against eating too soon Praepropere – thought to mean eating breakfast – in what was called the sin of gluttony. In addition to Praepropere, other methods of attaining the feat of gluttony, according to the Saint, include Nimis: eating too much, Forente: eating too fervently, amongst others [2]. If nothing is to be said about the spirituality driving such submission, everything has to be said about how modern science has proved the Saint right.

For St. Aquinas and medieval Christians, however, fasting is a marker of a successful, auspicious battle against the flesh, which ultimately is the driver of sin. All that was needed was a light dinner (their dinner is our lunch) and a heavier supper (their supper is our dinner).

Here is St Aquinas in his famous Summa Theologiae:

“Gluttony denotes inordinate concupiscence in eating. Now two things are to be considered in eating, namely the food we eat, and the eating thereof. […] the inordinate concupiscence is considered as to the consumption of food: either because one forestalls the proper time for eating, which is to eat hastily (thought to be speaking to not skipping breakfast) or one fails to observe the due manner of eating, by eating greedily.” [3]

But one wouldn’t be surprised at some diversity in the acceptance of the breakfast skipping admonition, as this Reddit discussion indicated. And one could say that pushing such admonition even with the label of something as grave as sin points out that some people are probably sneaking in some breakfast before showing their faces at noon prayers or something. Anyway, it’s pretty much believed among food historians that at certain times during the Middle Ages, especially at the early stages. Only two meals were had.

And what of the folks who lived before the Middle Ages? The Ancient Romans ate breakfast, which was called jentaculum [4]. Consisting of meals such as egg, bread, olive, and the like – mostly left over from the previous night.

On the other hand, in sixteenth-century Europe, physicians are recorded to advise against eating breakfast except if you are a member of the group exempted as stated earlier: laborers, children, and the old [5]. This is some three centuries or so after Aquinas.

While Aquinas attributed ‘eating too hastily’ amongst other ‘glutonic’ sins, leading to spiritual apathy. The physicians in the sixteen century had a much different justification for such an admonition.

They believed that before you get another food into your belly, the last meal must have been digested, and they earmarked some 6 hours or so for this digestion to occur. So, say you eat your first meal at 11 am (dinner), then you play around and come back for supper at 6 pm – you are certified to be in good standing. One should expect a solid early morning meal to be had, but not so fast, according to those bloody smart physicians.

They somehow figured out that while enough time has passed, exercise is the only thing that is missing, which is essential to ‘purge the body superfluities.’ The heat generated from the exercise is thought to help digest the food, as the digestive system can be slow-moving in the morning. So, the physicians advised having a few hours fast in the morning before eating [6] (It goes without saying that their reasoning is obviously wrong).

However, in 17th century Europe, a telling series of events occurred that began to break the moral bond of skipping breakfast. It was a ‘war’ between the Jesuits and the Dominicans about, of all things, chocolate. The Dominicans were against chocolate consumption during periods of fasting (which was becoming a thing), while the Jesuits were for it, perhaps because they were cacao traders.

The controversy deescalated to the point where a lady named Dona Magdalena de Morales assassinated one Salazar, bishop of Chiapas, who sided with the Dominicans. In the end, the pope at the time, Alexander VII, came through with a papal decree, namely: Liquidum non frangit jejunum, in English: liquids do not break the fast [7]. This, one can argue, broke the barrier toward breakfast consumption. (Even up until today, especially in some Christian quarters, people speak of dry fast or wet one.)

At some point also in the same century, it appears that the ship had left the shore as the diary of a 26-year-old civil servant Londoner named Samuel Peyps suggested. Conveniently the entirety of the diary has been placed on the internet today at pepysdiary.com, and a quick search for breakfast in his diary entries brought at least 46 instances.

The king of breakfasts

By the time we got to the Victorian era, with the second industrial revolution at hand, there was already a reversal from eschewing breakfast as we saw in the Middle Ages to even extolling it in the 19th century [8]. There we had the emergence of the middle class, who had to go to the office, and having a meal just before rushing out turned out to be a great idea, except that it wasn’t. Increasingly less farm work, less hard labor work, increasingly fewer places to walk to, and for some reason, we needed more food.

But the history lessons on breakfast are not yet complete without talking about the Kelloggs and Posts of this world. Coming straight outta the Clean Living Movements around the mid-19th century in America. If anything is to be said, this is where our modern breakfast cereals originate from.

Breakfast then was too rich, ‘unclean’ and dense, so there was an attempt to clean it up with something light. However, the movement was by no means restricted to culinary innovation, for example, the Jacksonian era (1830-1860) of the movement sowed the seeds that led to the emergence of Christian ministries like the Seventh-day Adventists and the Mormon church.

John Harvey Kellogg, a Seventh-day Adventist, together with his brother Will Keith, in 1894 invented the breakfast cereal – corn flakes, of which a patent was issued on April 14, 1896.

Another fellow C.W. Post, despite Kellogg’s patent, was said to have stolen his recipes while taking a tour at the facility and subsequently founded the Postum Cereal Co., a top competitor to Kellogg’s. This invention and the cereal flakes revolution that came afterward completely changed the breakfast landscape in America and, subsequently, the world.

And then they started pouring sugar into the damned thing: Will Kellog somehow figured out that adding sugar to the flakes shouldn’t be a bad idea; in fact, he thought that would be a game changer to drive up sales. John disagreed, so Will left and started the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company in 1906, which became what we know today as the Kellogg company. This move perhaps can be taken as the first derivative of our descent, as a civilization, into the hell of sugar in breakfast and pretty much everything.

Friends. We moved from not eating breakfast in the Middle Ages to now eating sugarcoated cereals and caloric-dense meals in the 20th and 21st centuries. There is little else to be said about today’s obesity epidemic.

Lean as hell

In my essay Go Hungry, I presented a brief overview of the biochemistry of fasting:

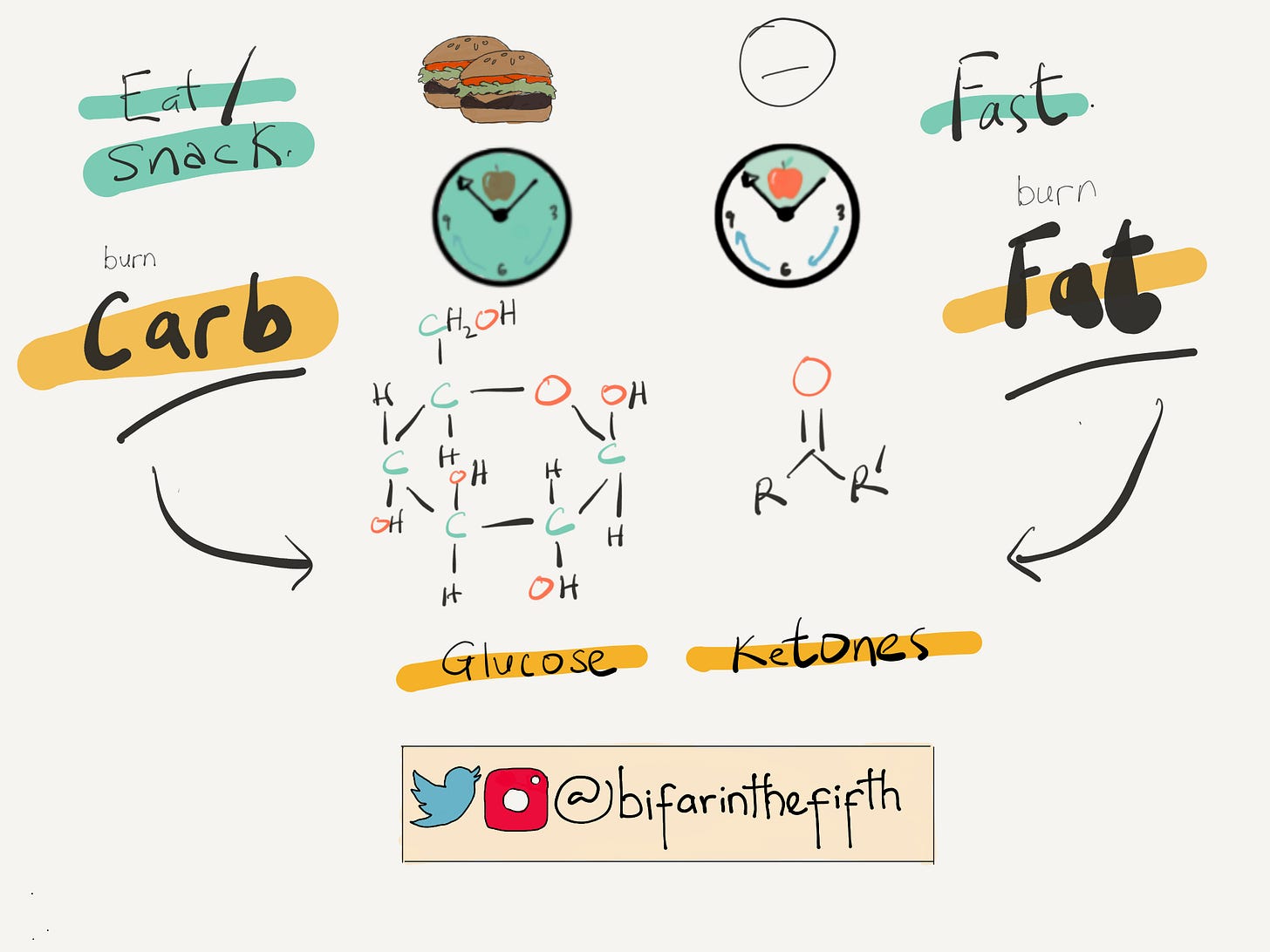

“…If you now so desire to fast, which usually leads to caloric restrictions, the glycerides (the fat we met just a few sentences ago) undergo hydrolysis to give fatty acids and glycerol. Fatty acids, in turn, are then converted to ketone bodies.

It then follows that when you are well-fed, your ketone body levels are low; however, during fasting starting from 8-12 hours, ketone bodies level will be on the rise because your body needs energy, and in the absence of glucose, it turns to fat. So, it’s no wonder people lose weight when calories are restricted.”

But it’s more than that, in the essay, I wrote about a longevity pathway that is positively affected via fasting [See essay].

Even the richest man in the world has something to say on the issue.

Now, if one must fast, it appears to me that the easiest way to do it is just to skip breakfast and go straight to lunch. There are other arguments out there about the modality of intermittent fasting, but not one single intelligible argument that I have seen against fasting for a healthy person [9].

References and Notes.

[1] Melitta Weiss Adamson, Food in Medieval Times (Greenwood Press) Pp. 155

[2] Aquinas on food.

[3] Summa Theologiae, Second Part of the Second Part, Question 148, Article 4. Link.

[4] Ken Albala, Hunting for Breakfast in Medieval and Early Modern Europe Pp. 20

[5] Ibid Pp. 22

[6] Ibid Pp. 22

[7] Anthony Cazalet, Papal puddings. Catholic Herald.

[8] Megan Garber, The Most Contentious Meal of the Day, The Atlantic. Essay

[9] Disclaimer: I am not a medical doctor; my essays are for educational purposes. If you want to make a major change in your diet (such as fasting), consult with your physician first.

Very insightful read!