[1] This essay serves a dual purpose. It’s one of my regular essay entries on the blog, in addition, it serves as an introductory essay for the theme of the upcoming MBB microgrant program.

[2] While I was researching this topic: watching videos and reading books, I came across a Saad Bhamla, a frugal science expert, who was one of the inventors of the paperfuge (more on this later). It turns out we work in the exact same building at Georgia Tech (I do not know him before then). Quite a pleasant surprise. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering department. I sent him an email, we had a chat, I told him about the upcoming MBB grant program, and he kindly indicated an interest in helping mentor a grantee (in the science/tech track), if the quality of project is excellent. Hopefully we can get a bright chap to seize this nice opportunity.

[3] There is an accompanying post to this essay - to give more, and detailed examples of frugal science, frugal tech, and frugal innovation. This essay is mainly about the ‘idea.’

Subject Area: Technology

Magnets, everywhere – New old cars – Developing the developing countries – Innovating for the street – And there are more.

Magnets, everywhere

One of the scientific instruments I used during my Ph.D. training in the United States cost a few million dollars. It’s called a nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer, popularly referred to as NMR by chemists.

NMR spectroscopy works by applying a magnetic field to a sample, which causes the nuclei in the sample to align with the field. Radiofrequency pulses are then applied, leading to the emission of signals that can be detected and analyzed. These chemical signals, if you will, are then used to determine the sample's chemical composition.

As part of my Ph.D. thesis, I used NMR to detect the chemical composition in urine samples to identify metabolites diagnostic of kidney cancer.

So why millions of dollars, you say? Well, the instrument can give you atomic resolution details for a molecule, and that’s just mind-blowing if you are familiar with this kind of stuff.

On the other hand, during my undergraduate degree program in microbiology back home in Nigeria, I did not get to set my eye on a single Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) instrument talkless of using one. In fact, I had to be taught how to use a pipette when I came to the United States for graduate studies. And I was no slacker – we did not have (easy) access to these basic laboratory instruments.

For the uninitiated: a pipette is a small handheld tool used in the lab to measure and transfer tiny amounts of chemicals and stuff.

On the other hand, PCR has been quite popular in recent years because of the COVID pandemic. PCR is a scientific instrument used to make many copies of a particular DNA sequence. This is done by using a special enzyme to break the DNA apart and then using a primer to attach it to a specific sequence. Then, the DNA is heated and cooled repeatedly to create many copies of the desired sequence.

These instruments are present in high school labs in developed countries, while many graduate programs in developing countries might not even have one that they can use routinely.

New old cars

Now. Talking about developing countries. Growing up in one, I had a popular misconception about wastage in the developed world. Wastage of a certain kind.

You see, virtually all the cars on our street are second-hand cars, called Tokunbo. In local parlance, it means cars from overseas. When an average person in a developing country tells you they bought a new car. She doesn’t really mean ‘new.’ What she meant was a new old car.

And when this car comes down to us, it turns out we could use it for years! And I couldn’t help but think of this as a waste – why sell off cars you can still repair and use for years?

It turns out that it is not a waste, after all. It is just the case that labor is more productive in developed countries. Repairing such a product in a rich economy will be a waste of (expensive) labor because alternate use of their time will provide more value than repairing a broken car.

To zoom in a little bit, given that most products are mass-produced with a great deal of automation, repairing individual vehicles cannot be automated in a similar fashion. This is because faulty vehicles are not faulty in the same way. As such, it will require more individualized labor attention, defeating the goal of the benefits derived from the economy of scales.

Developing the developing countries

The lack of scientific instruments for quality scientific research and the predominance of used, battered, and patched taxi cars on the roads, are not the only manifestation of a malnourished economy.

Again, let’s take the most populous black country, Nigeria. An estimated 70 million people in the country live in extreme poverty (data accessed Nov 6, 2022). Extreme poverty is defined here as less than $1.90 in income per day – a headcount index.

If we want to be more rigorous – which we should be, we ought to use a multidimensional poverty index that considers access to education, healthcare, and standard living conditions such as electricity and drinking water. Friends, according to Nigeria’s national bureau of statistics, 63% of Nigerians are living in poverty.

That is about 133 million human beings.

Again, friends, this is the entire population of the United Kingdom, Portugal, Belgium, Netherlands, Hungary, Switzerland, and Greece put together – and there might still be some room for a couple of millions. These people live without basic amenities like stable electricity, healthcare, or drinking water.

Now please tell me how you are supposed to use an NMR, a microscope, or manufacture your cars if you don’t have stable electricity.

So, what is the fate of hundreds of millions of people across the world living in extreme poverty?

Any well-meaning person would want the rapid development of developing countries. But in the meantime, what is to be done? One of the auspicious options is frugal innovation. Where resources are scarce, use must be prudent. That goes without saying, and that is what frugal innovation entails.

Innovating for the street

Many diseases/infection diagnoses, such as anemia, malaria, and HIV, are made with blood samples. And a first important step in the process is separating blood into its different components. This is done by spinning the blood sample in an instrument called centrifuge – making it easy to identify and analyze different cells and molecules in the blood.

(As a side note, the centrifuge spins really, really fast.)

It goes without saying that a centrifuge is a mainstay in modern medical laboratories. However, there is a problem. A centrifuge is expensive (it can cost thousands of dollars), it can be heavy, and you need electricity to power them.

Forget about the cost for a second; with 940 million people without access to electricity worldwide, they can only dream of getting a timely, life-saving diagnosis of anemia or malaria.

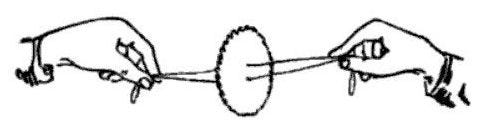

Comes in the Whirligig – also called ‘buzz toy.’

A small, spinning toy that is typically made of wood or metal. It has a long handle (a string) that is attached to a central disk. Amongst the Yoruba people of West Africa, we call it Kana-Kana. It has been around for centuries, and it cuts across cultures. In fact, I remember playing with it as a young child.

It turns out that a few years ago, a team of researchers adapted a whirligig as a centrifuge. And what was the result? A very low-cost (<$0.20), lightweight (~2 g) paper centrifuge that can achieve speeds of up to 125,000 revolutions per minute. They called it the paperfuge, and like the Whirligig, it is human-powered. In their paper published in 2017, they demonstrated that it could effectively and quickly separate plasma from whole blood and isolate malaria parasites.

This is frugal innovation at its best.

The paperfuge is not only dead cheap but also does not require power (See patent). This will not only make it possible to do diagnostic tests at the point of care in places where resources are limited, but it will also be tremendously useful for science education.

And there are more

When I was an undergrad, there was very little access to microscopes, even as microbiology students. There are many more students than there are available working microscopes. As a result, many of us couldn’t even operate one successfully.

So, I was naturally impressed when I read about the foldscope. A microscope made of paper that can be assembled in less than 10 minutes. All with a cost of less than a dollar.

It should be noted that frugal innovation doesn’t have to be sophisticated. It could be as simple as using plastic bags to save premature infants.

Preterm and low-birth-weight infants can be significantly impacted by hypothermia. When babies are born prematurely, their bodies are not as developed as they should be. This can cause problems with their ability to regulate their body temperature as it can drop quickly, leading to hypothermia. And if there are no quick interventions, the death of neonates is not unlikely.

It turns out that something as simple as plastic bags can save lives. Here is a conclusion from a randomized control trial conducted in Zambia:

“Placement of preterm/low birth weight infants inside a plastic bag at birth compared with standard thermoregulation care reduced hypothermia without resulting in hyperthermia, and is a low-cost, low-technology tool for resource-limited settings.”

A meta-analysis consisting of 34 trials involving 3688 newborns supported this claim.

At the risk of repeating myself, frugal innovation is the art of doing more with less and for many more people. And with the various examples I adumbrated above, if anything, one is left captivated and inspired.

This is the reason I have decided that the 2022 Mary Batatola Bifarin (MBB) grant program will be strictly open for applications on frugal innovation. And for the medical/clinical applicants, preference will be given to proposals for “frugal” healthcare projects.

See part 2: Examples of Frugal Innovation